Edgar Miller’s Influences:

Jane Addams’ Hull-House & The Blending of High & Low Arts

Booth of the “Immigrants’ Protective League” organization founded and supported by the Hull-House, at a conference in Chicago. Mural and decorative art by Edgar Miller. Booth hosts unknown, c. 1920. Photo by H. A. Atwell, from the Edgar Miller Legacy archive.

One of Chicago’s greatest social activists, Jane Addams had a significant influence on Edgar Miller’s early career. Though best known for her storied career in social work and women’s suffrage, Addams’ imprint on American art history and the development of Chicago as a community-based center for artists from around the globe cannot be overlooked. Through the development of Hull-House, one of the country’s earliest settlement houses founded in 1889, Addams brought a new socially-rooted sense of creativity and culture to the urban fabric of Chicago. With the world at the apex of the Industrial Revolution and with exponential economic growth in urban centers across the United States, there came with it the incredibly brutal working and living conditions subjected upon working class people and immigrants who migrated to the cities to make a life for themselves. Hull-House was established with the goal of educating and empowering the poor and disadvantaged, both for their own fulfillment and to help alleviate the city’s swaths of abject poverty.

By 1917, when a young James Edgar Miller arrived in Chicago, Hull-House had grown from a settlement home to a full-fledged community center offering counseling, childcare, language classes, employment placement, and artistic exhibitions of theater, music, and artisanal crafts. Now a whole city block of buildings made up of studios, classrooms, living quarters, offices, a gym, and more, the Hull-House was the perfect place for young artists to connect with their newfound city. One of Hull-House’s innovative programs was educating its residents on artisanship, especially inspired by Mexican pottery and craftwork.

Photo of Hull-House settlement apartments building exterior at 824 Halsted Street where Edgar Miller boarded and worked upon first arriving in Chicago in 1917. 335 S. Halsted St. in Chicago, shown here circa 1910s. The house number was originally 335 S. Halsted Street and was later changed to 800. Photo courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, c. 1918.

Redefining the High & Low Arts

At the time, the art world was even more stratified than it is today, with one type of “high art” of classically-inspired painting and sculpture, and the “low arts” which consisted of the so-called decorative arts, such as ceramics, textiles, and glasswork, commonly produced by nameless laborers (also predominantly by women). As a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, an idea emerged in the 1800s calling itself the Arts and Crafts movement, wherein the low arts were reconsidered and deemed more worthy than originally considered, and wholly necessary to establish any society’s true artistic culture. People like Jane Addams saw an opportunity to use this new movement to advance her mission of improving the lives of the working class and poor.

Having traveled all the way from Idaho Falls, Idaho with few possessions to his name, Miller was a student who was eager to start his career and learn about art. Having grown up on the western frontier, Miller’s conception of art was always more of craftwork and artisanship. He never personally distinguished between the high fine arts and low arts of handicrafts. Taking a room while paying a modest weekly rent fee before finding his own place in Chicago, Miller would have immediately come into contact with a network of educators and artists that participated in the Hull-House’s cultural and social work who serendipitously were of like minds when it came to high and low art distinctions. He purportedly met Sol Kogen, his main partner on the Handmade Homes, at the School of the Art Institute (SAIC) around the same time, but Kogen was also around the Hull-House and knew Addams well from growing up in the nearby Maxwell Street area and attending classes at the center as a teenager. Both Kogen and Miller referred to Addams as an influential mentor. When the two friends left SAIC abruptly, along with a group of other artists who deemed themselves “the Independents,” it was Addams who lent them extra studio space at Hull-House to work and gave them special attention, and helped form an ethos among the art group that would formalize and express their feeling about art philosophy for the rest of their careers.

Young men working in the Hull-House woodshop in 1911, learning useful trade skills and craftwork. Photo by Essanay Film Mfg. Co.

Hands-on ceramics art class for young immigrants, c. 1920. Students were often encouraged to incorporate cultural influences. Photo from the Jane Addams Memorial Collection.

A sculptural art class at Hull-House, c. 1913. Adolescent boys and girls were often segregated during classes. Photo courtesy of Chicago Tribune Archive.

Younger children arts class, often facilitated by teenage or younger resident artists, c. 1922. Photo from the Chicago History Museum.

By cultivating an industriousness and professionalism among Chicago’s growing immigrant community, Addams and her group of classically educated instructors developed an ethos of social improvement and equitable sharing of resources. The Hull-House Kilns were by then an important part of the settlement house community, having been successfully founded by SAIC professor Myrtle Meritt French only a few years earlier; and the arts programs at Hull-House was being supported by fellow professor, and ethnic art enthusiast Morris Topchevsky. French’s establishment of pottery studios along with the kilns proved to be a revitalizing and serendipitous project for the community. Under the auspices of Hull-House’s community support, an unimaginably prolific braintrust developed between the more institutionally, classically trained potters and the culturally diverse immigrant artists with their own brand of craft knowledge and aesthetics. Further blurring traditional boundaries at the Kilns, the division of masculine artisanal work and feminine handicraft were for the most part erased. The individual pieces of pottery produced at the Hull-House were exquisite works of art individually; altogether, they were essential resources for the community. The Hull-House Kilns created everything from earthenware flatware, to hand-painted tea sets, and color-glazed containers of assorted sizes; all sold to raise funds for tenement services, and also distributed amongst community members for daily use. And the ideology behind Hull-House’s arts programs was quickly recognized as one of radical inclusion and democratization of art production.

Edgar Miller decorated tea service, c. 1935 with embellishments and motifs reminiscent of glazing styles from Hull-House catalogs.

It’s also worth noting that the Hull-House was constantly abuzz with some of the most talented artists and teachers of art and design in the city, including: artist Enella Benedict (founder of the Hull-House’s arts program), ceramicist Myrtle Merritt French, artisan Jesús Torres, and artist-designers Alfonso and Margaret Iannelli. Alfonso Iannelli, another of Miller's mentors and later his employer, often taught classes at Hull-House, and it is entirely possible that it was at the Hull-House that Miller and Iannelli first met. This confluence of influences became the sparks that jump-started Miller’s career as an artist-designer, as discussed in the expository work by Barbara Jaffee. It was through the collaboration of all of these artists, artisans, and crafters, through the point of view of creative designers like Miller and the Independents that effectively blended the ideas of high art and low art. The Hull-House eventually became a center where masterpieces on the physical scale even as small as teacups were being produced in its kilns through the communal work from people of diverse backgrounds and talents.

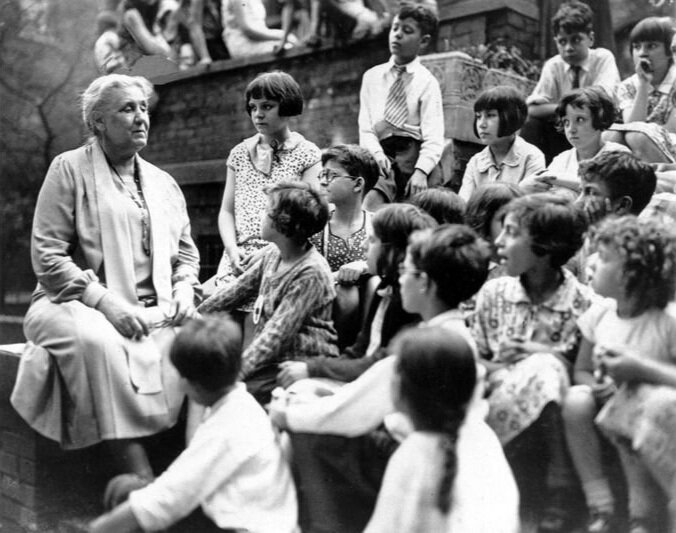

Jane Addams speaking directly to a class of young Hull-House students, c. 1932, exact date unknown. Photo from AP.

The Legacy of Jane Addams

Jane Addams passed away on May 28, 1935, leaving behind a legacy of reformed educational and social systems that spread widely across the US during the Depression. Unfortunately, many of Hull-House’s programs were hit hard during the economic downturn, losing much-needed funding and sources of support. In a beautiful twist of fate, though, in 1938, Chicago named its first public housing project after her, and it was Edgar Miller who was named the artistic designer. For this project, Miller designed and oversaw the sculpting of the Animal Court, an assembly of massive boulder-like sculptures for the building’s central courtyard, as well as other embedded artistic details (which sadly do not remain extant). These sculptures were the memorable objects for many of the members of the housing project’s younger generation.

Sculpture of a bear at Jane Addams Homes (1938). Note the other decorative artwork in the background, formed by what appears to have been chiseling and carving out of the brick facades.

The concept of modern public housing was an entirely new idea, and inclusion of large scale artwork in such an intentional way tangibly connected the philosophies expressed in the Arts and Crafts Movement and Jane Addams’ Hull-House initiatives. It should come as no surprise that Miller’s Animal Court became a favorite gathering place for the Russian-Jewish, Polish, Italian, German, and later black and Latinx families who lived at the Addams Homes for many decades to come. Today, the sculptures are being conserved by the National Public Housing Museum with plans to fully restore and include them in the museum’s central courtyard, a memorial to the legacy of Addams’ work and the thousands of Chicagoans she helped get started in a city of possibilities.

One of seven Animal Court sculptures, currently in conservation at the Conservation of Sculptures and Objects Studio. Photo by Alexander Vertikoff.